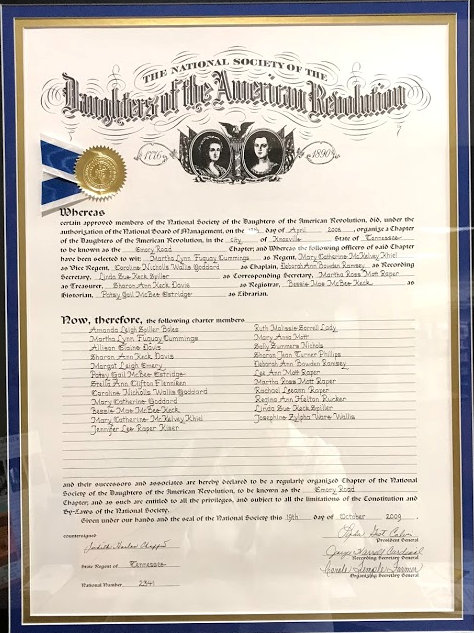

In December 2007, Martha Cummings, Mary Cay Khiel, Caroline Goddard, Sharon Davis and Deborah Ramsey met for lunch and discussed their desire to start a new DAR chapter which would be vibrant and active. Martha Cummings was approved in the same month by the Executive Board, to be an organizing regent. These ladies worked to get family and friends’ applications completed and approved. On April 12, 2008 the Emory Road Chapter was organized with eighteen members. Members attended the TSDAR State Conference in May 2008 as the newest chapter in Tennessee. On October 25, 2009 a chartering ceremony was held at the East Tennessee Historical Society. The coincidence that the Emory Road Chapter was designated as 3-131 TN and Emory Road is Tennessee State Highway 131 is not to be forgotten.

Emory Road Chapter is named after one of the most well-known roads in Knox County,Tennessee. The original “Emery Road” followed closely some sections of an old Indian trail from the area now known as East Tennessee to what is now Middle Tennessee. This trail was known as Tollunteeskee’s Trail. Long hunters used portions of this trail as early as 1766 when James Smith returned from a long hunt using the route. The first formal authorization to “cut and clear” a trace for a direct route to the Cumberland settlements occurred in 1785 when the North Carolina legislature provided for a force of 300 men to protect the Cumberland settlements. These soldiers werecharged with cutting and clearing a road, by the most eligible route, from the lower end of the Clinch Mountain to Fort Nashborough. More direct and shorter than the Wilderness Road, it would accommodate expected increases in immigration as Revolutionary War veterans claimed their land warrants.

The Cherokee claimed the territory between the Clinch River and a treaty line west of Standing Stone – modern day Monterey. They disputed the right of the white settlers to use this trail through their country without permission. The Cherokee always insisted that the government build “one road” from Washington District to the Cumberland settlements, rather than many traces using various routes.

In 1787 North Carolina legislators approved a second road act, which again ordered a road cut and cleared from the south end of Clinch Mountain to Fort Nashborough. The Cherokee continued to resist white settlers crossing their land and demanded that tolls be paid. Those who refused risked losing their lives.

The Emery Road is an historic route in the settlement of America, both the Indigenous settlement and the colonial settlement. However, this road is far more ancient than Colonial America. These roads were first laid down by the Pleistocene megafauna, mastodons and mammoths, as they migrated season to season, and from saltlick to saltlick. These animals over deep time wore down paths of least resistance to all points in America. These paths were later used by Ice Age hunters to hunt these great beasts, and later still when man became agrarian, to trade the essential commodity of salt. Eventually these paths became our highways and superhighways. Often the newer routes vary slightly from the original routes, thus leaving traces of the ancient routes visible today. Such is the case with the Emery Road.

The path that became the Emery road was cut in 1788 under orders of the North Carolina Legislature. It started at a road that was cut along the Great Warriors Path near Blaine, and ran through Halls, Powell, and Karnes before hopping the ridges and passing by the David Hall cabin in the Bull Run Valley. It crossed the Clinch River where the Oak Ridge Marina is today and passed along Emory Valley Road, then cutting through to the Oak Ridge Turnpike at Manhattan Place. It crossed the Rock Pillar Bridge and up along Raleigh Road and Illinois Avenue and out through Oliver Springs (Winter’s Gap), and on to Nashville. Many of the folks came down this road, or the later reroute of the Walton Road (now known as Kingston Pike).

Often billed as the first road in the state, the Emery Road, and its alternate routes, are part of a system of early roads, known as the Great Stage Route that connected the Nation with its capitol: first Philadelphia and later Washington, DC. The Emery Road would become one of the most

important settlement roads in our Nation’s early history. Many of our ancestors who settled the Southeast and Texas traveled down this road, some stopping at Nashville, while others went on down the Natchez Trace to the Southwest.

Before the North Carolina legislature ordered Peter Avery to cut the Emery Road, it was known as Tahlonteeskee’s trail. Chief Tahlonteeskee was brother of Chief John Jolly, both leaders in the Chickamauga Tribe that was made up of remnants of several Indigenous tribes. Tahlonteeskee contentiously charged tolls to pass down the Emery Road. Those who refused to pay the tolls paid the ultimate price. Tahlonteeskee eventually negotiated a treaty with James Glasgow, John Hackett and Littlepage Sims for a change of path southward along an alternate route, called the Walton Road, where the militia could escort and protect the settlers between Sawyer’s Fort, Fort Adair, White’s Fort, Fort Southwest Point and on westward. The Militia then paid the required toll to the Indians.

The Emery Road continued to function as a principle route up until the 1940s, but not as the main route that it had been. It changed from a ford at the Marina to Black’s Ferry at the community of Clinch River, and later to the Edgemoor Bridge, and finally to the Solway Bridge. It continued to be one of two main roads in southern Anderson County, the other being the Hogoheegee Trail, or the Powell River Road, which became Highway 61 and later the Oak Ridge Turnpike. The two roads crossed at the crossroads in Robertsville. It was here in the mid1800s that they constructed a wooden bridge over Cross Creek that both roads used instead of the rugged creek fording that had been required. This rock pillar bridge still stands about sixty yards north of the Oak Ridge Turnpike bearing evidence of the ancient passing of the Emery Road through here. The wooden structure on the rock pillars was replaced by a concrete one in about 1900. The Emery Road finally was supplanted by Tennessee Highway 62 in the 1950s.